Birmingham, Alabama

At least fifteen sticks of dynamite exploded in the basement of the 16th Street Baptist Church as Sunday school classes were being held here today, killing four Negro schoolgirls and injuring 23 other Negroes, some seriously. Later, police shot dead a Negro youth after he threw stones at passing cars. Another Negro boy, aged 13, was shot dead while riding a bicycle.

The church was the starting point in the summer for marches by Negroes in protest against segregation. Today the inside of the building was a complete chaos. The church clock stopped at 10.25 a.m. The pulpit was shattered. A damaged cross lay among the rubble. Glass, some of it bloodstained, covered the pews and the choir stalls.

The force of the explosion was such that concrete blocks were torn loose and hurled outwards, windows were blown out of shops and houses nearby, and several cars parked outside were destroyed.

In the unfinished Sunday school lesson this morning the children were reading from the Gospel of St. Matthew: “But I say unto you, love your enemies.” Tonight only one stained glass window in the church remained unbroken: it showed Christ leading a group of little children.

One witness said he saw about sixty people stream out of the shattered church, some bleeding. Others emerged from a hole in the wall. Across the street a Negro woman stood weeping. She clasped a little girl’s shoe. “Her daughter was killed,” a bystander said. Two of the dead schoolgirls were aged 14 and another aged 11. One of the children was so badly mutilated that she could only be identified by clothing and a ring.

Mr. M. W. Pippen stood outside his damaged dry cleaning shop opposite the church. “My grand baby was one of those killed,” he said. “Eleven years old. I helped pull the rubble off her… I feel like blowing up the whole town.”

Other people had lucky escapes. Miss Effie McCaw, a 75-year-old Sunday school teacher, said she was taking a class of five children in the basement when the explosion occurred. “I told them to lie down on the floor,” she said. “None of us was hurt.”

One Negro man, Robert Green, aged 24, said he was driving past the church when the explosion occurred:

“I was only about thirty feet from the church. I didn’t notice anyone around the church, but I wasn’t paying particular attention. There was a big boom and I was knocked out. Glass was flying everywhere. When I came to, my car had stopped and I saw people coming out in front of the church. A woman came out from the hole in the wall. There was blood on her face.”

State troopers and Birmingham police were alerted to stop a car with two men seen near the church at the time of the explosion. The Governor of Alabama, Mr George Wallace, who is against integration, offered a $5,000 reward for the capture of those who caused the explosion, and the Department of Justice called in detectives from the Federal Bureau of Investigation.

Soon after the explosion a white man with a Confederate flag flying on his car drove into the area. Police quickly took him into custody.

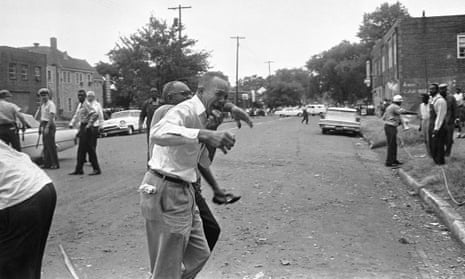

All available Negro ambulances were sent to the church, and as police and firemen pulled at the rubble in search of more bodies, crowds of angry, weeping Negroes gathered near by. They began throwing stones at police, who sent for riot equipment.

The Rev. John Cross, pastor at the church, took a police megaphone and walked to and fro, urging the Negroes to leave the area. “The police are doing everything they can. Please go home,” he pleaded.

Later Governor Wallace ordered 150 State troopers into the area at the request of the police chief, Mr Jamie Moore, who said he feared reprisals by Negroes. Units of the National Guard which have not been federalised were also alerted.

The Rev. Martin Luther King, the Negro leader, said in Atlanta, Georgia, “Our whole country should enter into a day of prayer and repentance for this terrible crime.” In a telegram to President Kennedy he said he would go to Birmingham to plead with Negroes to refrain from violence.

He added that unless the Federal Government took immediate steps there would be in Birmingham and Alabama “the worst racial holocaust this nation has ever seen.”

The bombing of the 16th Street Baptist Church was a pivotal moment for the American civil rights movement. The FBI identified four suspects, all Ku Klux Klan members, but no charges were brought at the time, though one, Robert Chambliss, was sentenced for holding the dynamite without a permit. Chambliss was convicted when the case was revived in 1977, Thomas Blanton in 2001 and Bobby Frank Cherry in 2002. Herman Frank Cash, the fourth suspect, died in 1994.

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion